Venezuela: How Monetary Mismanagement Contributed to Maduro’s Weakness

The outcome of Sunday’s election in Venezuela is anyone’s guess. For one thing, referring to the exercise as an “election” is hardly precise because most voters will not be allowed to elect their candidate of choice. In 2023, the Chavista regime banned opposition leader María Corina Machado from running for office for fifteen years. Last October, Machado won an opposition primary with over 90 percent of the vote. The regime even prevented Machado’s chosen successor, octogenarian academic Corina Yoris, from registering as a candidate before the official deadline.

The opposition thus had to settle for supporting the pre-approved candidacy of Edmundo González Urrutia, an obscure, 74-year-old former diplomat who last held a post—as ambassador to Argentina—in 2002. But Machado’s massive rallies across Venezuela are still the campaign’s primary spectacle; she often has to elude the socialist regime’s roadblocks and other impediments—such as the arbitrary imprisonment of her staffers— just to speak to eagerly expecting crowds.

Due to Machado’s support, González Urrutia is due to win in a landslide on Sunday against Nicolás Maduro, the unpopular socialist autocrat who has held power since 2013. This is according to practically all opinion polls. The question is whether the Maduro regime will accept an adverse result, or even if it will allow an electoral defeat to materialize. Notoriously, the regime controls the National Electoral Council, which presides over a fully electronic voting system that has elicited constant suspicions of fraud. According to Lewis Pereira, a Venezuelan sociologist,

“Testimonies from former government intelligence agents, who later defected, suggest that the government, apart from announcing fraudulent results, has introduced false national identification cards into the system. The estimate is 4 million false ID’s. It seems that, when the government wants to provide authentic data, it manipulates the results in its favor by several million votes.”

Beyond the possibility of fraud on a colossal scale, consider Maduro’s incentives to leave power or rather the lack thereof. With the US State Department offering up to USD $15 million for information leading to his arrest or conviction due to drug trafficking charges, and the International Criminal Court probing his government for crimes against humanity, Maduro can hardly look forward to a quiet spell in opposition. The same applies, of course, to his cronies, for whom power, jail, or bitter exile appear to be the main options at hand. Hence Maduro’s recent threat of a bloodbath and a civil war if the opposition wins the election. Hence also the rumors of the offer of an amnesty in exchange for a peaceful transfer of power, and of Maduro’s alleged plans to flee to Cuba or even Turkey. For the time being, these are matters for speculation.

Far less speculative are the root causes of Maduro’s current predicament. It is thus fitting to ask how the once-formidable Chavista regime, which was so certain of its grip on power that it attempted to export its revolution aggressively across the region, ended up with its back against the wall on its home turf, even in Hugo Chávez’s old regional strongholds. The following graphs, pertaining solely to inflation and currency devaluation, will provide some hints.

Inflation

High inflation rates in Venezuela during the 1990’s are an underestimated cause of Chávez’s eventual rise to power. Even so, the “Agenda Venezuela” economic plan, which Rafael Caldera implemented toward the tail end of his second presidency (1994–1999), got rid of fiscal deficits and reduced the annual inflation rate from 99.99 percent in 1996 to 35.8 percent in 1998, the year when Chávez won his first election.

The downward trend continued during Chávez’s first years in office. While the central bank maintained some independence, the inflation rate reached 12.5 percent in 2001, the lowest level since the 1980’s. Nonetheless, public spending spiraled out of control and Chávez took control of Venezuela’s central bank in 2007. The following year, José Rojas, who served as Chávez’s finance minister before turning into a critic, predicted that the Venezuelan Central Bank’s loss of autonomy would lead to a financial crisis. The warning turned out to be understated.

As Chávez depleted international reserves and expanded the money supply to finance deficit spending, inflation inevitably rose and remained in double digits. By 2013, the year of Chávez’s death, inflation exceeded 40 percent per annum for the first time since 1997. Nor would it recede from that level. The inflation rate surpassed triple digits in 2015. By 2017, the year when Maduro repressed massive, student-led protests against his regime (hence the ICC’s probe against the autocrat), inflation stood above 430 percent. Yet this paled in comparison to the hyperinflationary phase of 2018 and 2019 when inflation reached over 65,000 percent and 19,000 percent per annum respectively. Such stratospheric inflation levels make the triple-digit figures of 2015–2017 and 2020–2023 seem mild.

It is a wonder, one might say, that Maduro’s hyperinflationary government currently maintains support levels above 20 percent, according to some opinion polls.

Devaluation

When Chávez took power in 1999, one dollar bought 595 bolivars, a price within the currency band that had been in place since 1996. Following the failed attempt to oust him from power in April of 2002, Chávez let the currency float freely, initially from a rate of 793 bolivars per dollar. In February of 2003, Chávez abandoned the short-lived free-floating regime, imposed exchange rate controls, and fixed the currency to the dollar at a rate of 1,600 for purchases, whereas the market rate had stood at over 1,800 bolívares per dollar.

Chávez blamed the bolivar’s glaring weakness on the large oil sector strike of late 2002. But, as economist Ronald Balza Guanipe wrote, public spending had increased by 50 percent in real terms (over 90 percent nominally) in a mere three-year period, while the financing of such largesse with oil revenues expanded the monetary base and “generated pressure over the exchange rate and the prices of goods and services.”

As the spread between the official and black-market rates grew, Chávez further devalued the currency in 2004, in 2005, and in 2010 (by a full 50 percent). Two years earlier, in 2008, Chávez had eliminated three zeroes from the currency, thus announcing the launch of the “strong bolivar,” a new currency. In early 2013, as he received treatment for cancer in Cuba, Chávez devalued the bolivar a further 32 percent. After the latter’s death, Maduro devalued by a further 37 percent in 2016, thus leaving the official exchange rate at 10 bolivars per dollar (or 10,000 according to the previous denomination).

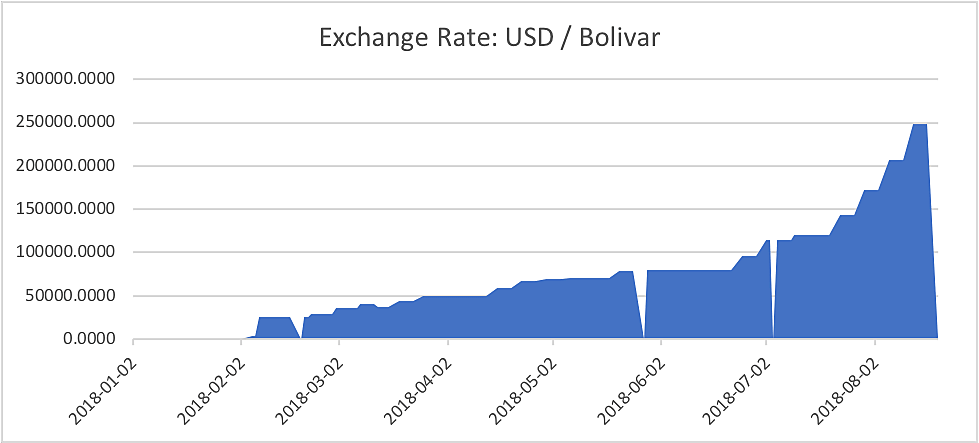

By December 2017, the Venezuelan currency had lost 92 percent of its value against the US dollar since December 2000. Amid the hyperinflationary bout of 2018, Maduro devalued the bolivar by a further 95 percent and pegged it to a new cryptocurrency called the Petro, purportedly backed by Venezuelan crude oil. With a single dollar buying over 248,000 bolivars—and a modest lunch selling for around 3 million bolivars—Maduro announced the removal of a further five zeroes from the currency in July 2018 (he removed yet another six zeroes in October 2021).

In effect, Chávez and Maduro had made Venezuela’s currency worthless, with street vendors selling woven goods made out of bolivar banknotes.

Naturally, Venezuelans did not sit idly as the socialist regime destroyed a national currency that had once been praised for its stability. Hence their adoption of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies; according to a 2022 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development policy brief, Venezuela ranked third in the world in terms of cryptocurrency adoption (with digital currency ownership as a share of the population standing at 10.3 percent, behind only Ukraine and Russia). Hence, above all, Venezuelans’ widespread adoption of the US dollar as their unofficial currency after Maduro was forced to relax Chávez-era exchange rate controls in 2018.

In early 2021, Reuters reported that over 50 percent of all transactions for basic goods in large Venezuelan cities—and 90 percent in cities close to the Colombian border— were being made in dollars or euros. Johns Hopkins economist Steve Hanke argued that the dollar had become Venezuela’s unit of account, since even bolivar transactions were calculated in dollar terms. As I wrote at the time, de facto dollarization provided Venezuelans with much-needed monetary stability. Today, it is evident that, though still incomplete, dollar adoption has helped to rein in thousand-plus-percent annual inflation levels, thus buying Maduro some time (nominally until Sunday’s election) at the very least.

In 1919, Vladimir Lenin told London’s Daily Chronicle that “the simplest way to exterminate the very spirit of capitalism is (…) to flood the country with notes of high face-value without financial guarantees of any sort,” a quote best known through John Maynard Keynes’s synthesis: “the best way to destroy the capitalist system (is) to debauch the currency.” And yet Venezuela’s recent experience—Sunday’s results notwithstanding— confirms that debauching the currency is also the natural way in which a socialist system destroys itself.

How else to explain the “Bolivarian Republic’s” forced entry into Latin America’s dollar zone, where people freely choose a relatively sound currency, much in the tradition of the bourgeois pitiyankis (roughly “Yankee lovers”) whom Chávez so often maligned?

Read the Cato-at-Liberty blog post here.