Twelve Graphs on Why Maduro Could Only “Win” by Stealing Venezuela’s Election

On July 26, I noted that the crucial question about Venezuela’s upcoming election was not whether Maduro would lose in a landslide, as he did according to serious exit polls and the National Electoral Council’s initial figures prior to an alleged blackout. Rather, the question was whether Maduro would accept the result. He did not.

At the time of writing, the regime, which controls the electoral council, has not produced evidence to back its claims that Maduro beat opposition candidate Edmundo González by a margin of 51 to 44 percent. Protests are erupting in Venezuela and several Latin American countries, including Chile, which is led by a left-wing president, refusing to recognize the election’s validity. It is now clear that Maduro’s plan is not to flee or negotiate, but rather to hold on to power by any means necessary.

Why are those means necessarily fraudulent, potentially also violent?

The following graphs will help explain why, according to fair calculations, around 65 percent of Venezuelan voters rejected Maduro’s government yesterday at the polls.

Inflation

Chávez took control of Venezuela’s central bank in 2007. When he died in 2013, Maduro inherited 40 percent annual inflation levels after a hefty rise in the previous decade. By 2017, the Chavista regime’s monetary mismanagement had left inflation at 438 percent per annum.

Mere triple-digit annual inflation levels—such as those that Venezuela is experiencing now— would seem low in comparison to the hyperinflationary period of 2018 and 2019, when the Chavista regime oversaw 65,000 percent and 19,000 percent inflation respectively.

Devaluation

Chávez constantly devalued Venezuela’s currency, as did Maduro when he took over. By 2017, the bolivar had lost 92 percent of its value against the dollar since 2000. As hyperinflation raged, Maduro further devalued by 95 percent and removed eleven zeroes from the currency in two years.

By 2018–2019, Chávez and Maduro had made Venezuela’s currency worthless; street vendors at one point sold goods woven from bolivar banknotes. Maduro was forced to remove currency exchange controls. By 2021, large parts of the Venezuelan economy were de facto dollarized.

Debt to GDP

When Chávez won his first election in 1998, Venezuela had a relatively healthy debt-to-GDP ratio of 30.7 percent. By the time of Chávez’s death in 2013, the debt had risen to the equivalent of 85.4 percent of GDP. Since 2015, Venezuela’s debt-to-GDP ratio has remained well above 100 percent, having reached a record level of 327.7 percent in 2020.

Per Capita GDP

High oil prices and Chávez’s deficit spending boosted Venezuela’s per capita GDP nearly fourfold from 2003 until 2012. A full bust would follow the boom. The Chavista model’s collapse and the oil bear market of the mid-2010’s pushed the country’s per capita GDP in 2018 to roughly the same level as 1984—this despite a population exodus. The same remains true today despite the sharp rebound in oil prices since the lows of 2020. Chavismo thus set Venezuela back four decades in terms of economic growth.

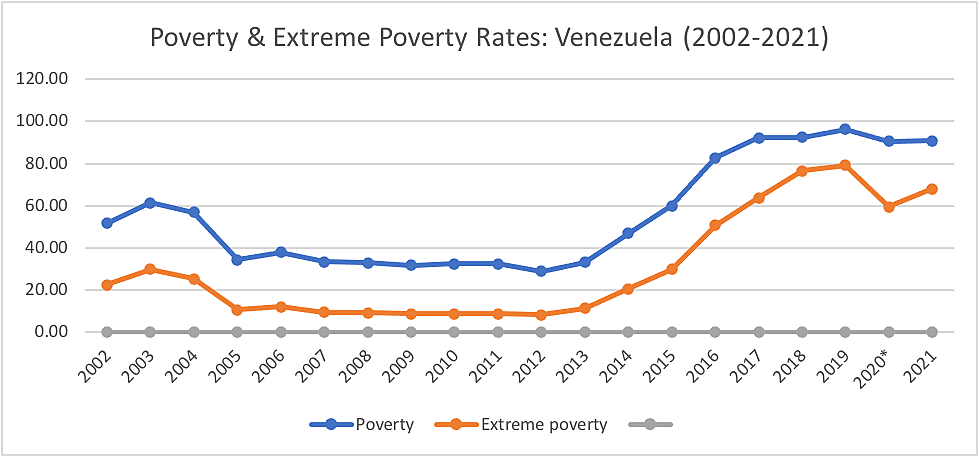

Poverty & Extreme Poverty

Through his extreme fiscal profligacy, fueled by debt and petrodollar income at the height of the 2000’s oil boom, Chávez created the mirage of a nation that was defeating poverty. By the early 2010’s, the poverty rate had dropped below 30 percent of the population and extreme poverty below 10 percent. Then came fiscal, monetary, and economic collapse. By 2019, 96 percent of Venezuelans lived in poverty and 79 percent in extreme poverty. In 2021, the Financial Times reported, “for the first time, the average Venezuelan is poorer than the average Haitian.” The formerly rich Venezuela had become Latin America’s poorest country.

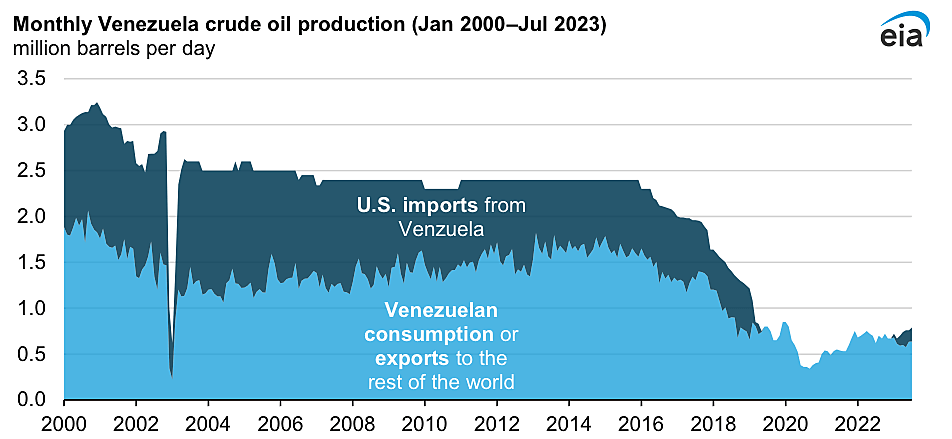

Oil Production

Venezuela sits atop the world’s largest oil reserves and, in the early 2000’s, was producing north of 3 million barrels of crude per day. Even after the oil-sector strike of 2002–2003, an attempt to prevent Chávez from seizing control of the state-owned oil company (PDVSA), and Chávez’s subsequent firing of 20,000 PDVSA employees (out of a total of 35,000), Venezuela produced over 2.5 million barrels per day. But decline set in as Chávez seized PDVSA, filled its ranks with his supporters, and used its resources for his “revolutionary” aims, for instance building social housing.

The poorly led company was unable to weather the oil bear market which began in 2014. Trump-era sanctions halted all oil exports to the United States, but Venezuela’s exports to the rest of the world also dropped precipitously, as did internal oil consumption. By 2019, Venezuela was producing well below one million barrels of crude per day, a figure that dropped to under 500,000 barrels per day during the COVID-19 crisis.

Chavista propaganda blames the collapse of Venezuela’s oil industry solely on US sanctions, but history has provided a curious point of comparison. Despite facing severe sanctions on its own oil exports since early 2022, Russia “has defied predictions of severe declines in its oil supply,” as Reuters reported at the end of 2023 (with Russian supply expected to remain steady in 2024). In Venezuela’s case, Bolivarian socialism, not sanctions, is the main culprit of PDVSA’s downfall.

Emigration

Venezuelans began to leave their country en masse in 2014. By 2022, 6.8 million Venezuelans were residing abroad, many of them as refugees. According to R4V, a platform of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration, there were 7.77 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants in the world in early 2024, with 6.59 million living in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Neighboring Colombia is the country that has received the most Venezuelans in the last ten years, at an astounding 2.8 million; Colombia’s total population in 2013 stood just above 46 million, according to the World Bank. Peru (1.54 million), Brazil (568,000), Chile (532,000), and Ecuador (444,000) follow. Outside Latin America, the United States and Spain have received the largest numbers of Venezuelan migrants. In 2019, a UN report estimated that Venezuela had already lost 10 percent of its population due to the exodus.

Political Prisoners

As in Cuba, whose regime Chávez admired and emulated, political repression has been a hallmark of the Chavista era, with a sharp rise in political prisoners during Maduro’s time in power. High-profile opponents of Chavismo who have been incarcerated include Leopoldo López, a party leader and local mayor in Caracas, and former Caracas mayor Antonio Ledezma, both of whom managed to flee Venezuela.

The number of political prisoners increased drastically in 2017 when the regime violently put down massive protests that arose after Maduro’s “dissolution” of the opposition-led National Assembly and the arbitrary arrest of opposition leaders. Although the regime has used the release of certain political prisoners as a bargaining tool in its frequent negotiations with the opposition, it targeted opposition leader María Corina Machado’s staff members for arbitrary detention during the recent election campaign.

Homicide Rate

Chávez had little intention of upholding Venezuelans’ liberty and property. Nor did he safeguard their right to life. Venezuela’s homicide rate rose sharply under his rule and that of Maduro, reaching a high of 63 murders per 100,000 inhabitants in 2014, according to official figures, whose accuracy has been questioned. The Venezuelan Observatory of Violence, an independent research institute, has constantly published figures that exceed those of the regime. The institute calculated the 2013 murder rate, for instance, at 79 per 100,000 inhabitants versus the regime’s 39 per 100,000.

As journalist Jeremy McDermott wrote in 2014, “Unfortunately the government claims that homicides actually dropped 30 percent in 2013 are so unbelievable that they must be discounted.” At 79 homicides per 100,000 people, he added, Venezuela “is still far away the most dangerous nation in South America, and trails only Honduras (with a rate of 86) as the most dangerous nation on earth.”

But the homicide rate has dropped considerably since the mid-2010’s, as the observatory’s own figures attest. In 2023, the institute reported 27 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, the lowest rate since 2001. According to one theory, mass emigration has lowered the murder rate because entire criminal groups have also left Venezuela.

Human Freedom

The Human Freedom Index measures countries’ economic liberty together with the degree of civil and personal freedom that they allow their citizens. The index, which measures human freedom in 165 countries since the year 2000, has tracked Venezuela’s descent into authoritarianism since the early stages of Chávez’s rule. From its initial human freedom ranking below the middle of the pack in 2000, Venezuela steadily deteriorated. In 2019, it fell to second-to-last place. Venezuela currently ranks last in terms of economic freedom.

Read the Cato-at-Liberty blog post here.